Analyst recommendations are littered with biases. They are unavoidable, especially when attempting long-range predictions. Inflation versus disinflation biases forms the foundation of nearly any forecast. It will influence your assumptions for expected return, the cost of funding, the economic growth inputs that will help determine sales projections, and vitally, the valuation assessments for that company, security, or building. Having a clear framework on the future of inflation is essential when forecasting the forward value of any asset.

The transitory versus permanent inflation debate is front and center of investment committees and central banks. However, investors have less clarity than they did in the past because they are unsure how central banks, especially the Fed and the ECB, will deal with these inflation pressures. Mandates have been clouded in the past decade. Prior to Mario Draghi and Madame Lagarde, former ECB President Jean Claude Trichet rigidly stuck to the single inflation mandate, which led to two policy blunders in 2008 and 2011 when he raised rates on the verge of two crises. He would argue that he was sticking to his remit and following the only mandate: inflation. That statement was true and was reflective of the deficiencies of the mandate itself.

Post the European debt crisis, Mario Draghi introduced a more comprehensive degree of flexibility in the conducting of monetary policy. It is tough to do whatever it takes to save the Euro if you cannot do whatever it takes. While European inflation remained benign during the Draghi era, it was clear Europe had entered a new phase of monetary policy, leaving the austerity of the Bundesbank in its wake. Massive balance sheet expansion and negative interest rates show just how transformative the policy shift has been. While the Federal Reserve has always had the flexibility of the dual mandates of full employment and inflation, negative interest rates in Europe show just how radical the change was.

Madame Lagarde took the transition much further when the 2020-21 strategic review incorporated climate change considerations into the monetary policy framework. While I would argue that the details are a little vague, it is clear that the ECB will be prioritizing the funding of climate infrastructure when considering future asset purchase programs. It is not a stretch to believe that the ECB will be monetizing hundreds of billions of dollars of green debt in the years ahead, effectively underwriting the climate infrastructure needs of the EU and engaging with global corporates to financially underpin their transition to carbon neutrality.

This is not the ECB of Jean Claude Trichet.

While we haven’t seen the same formal pivot by the Federal Reserve, there will be mounting political pressure to move in a similar direction to the ECB. I will assume a similar approach in the years ahead, not just by the Fed but every major central bank in the developed world. This should be applauded as there is no more vital and immersive global priority than decarbonization. All governments and agencies need to be on board to achieve the lofty goals required to save our planet. Coordination and radical measures will be required, not solely due to the enormity of the challenge but the path to a decarbonized world will take decades and create unprecedented economic friction. As a client said to me recently, there is no magic wand.

Economic friction causes inflation

I believe inflation comes from one source, and that is due to disruption to the global supply chain. Be it in commodities or goods shipped around the world, when supply is interrupted, prices can spike. The global supply chain works incredibly well. The efficiency of everything from semiconductors to bicycles is a marvel. However, as COVID proved, when things go wrong, they can go horribly wrong. Be that spiking container costs, fertilizer prices, or a cup of coffee, supply dislocations driven by worker shortages, a port disruption, or the closing of the Suez Canal, it is the inability to deliver goods on time that forces companies and consumers to scramble and pay higher prices.

Those of us who advocate for transitory inflation will argue that supply chain efficiency will eventually return, and the sand that has been thrown into the gears of global trade will disappear and return the world to equilibrium. The path to economic normalization could easily be described as a return to a world where supply and demand balance. Some sectors will take longer. You do not just flick a switch and develop more semiconductor capacity. While I believe that much of the inflation we are witnessing is transitory, some sectors will see more persistent pressure than others.

Regular readers will have picked up on a subtle yet significant change in tone regarding my views on inflation. I believe that much of the inflation we are witnessing will be transitory, or more specifically, inflation due to COVID-induced supply disruption will be temporary. However, in the quarters and years ahead, I see a risk of sharply higher commodity prices due to the energy transition.

COVID era price spikes will eventually disappear, but the world will be left to deal with the true inflation challenge of this decade, which is the demand for the industrial metals and rare earths required for decarbonization.

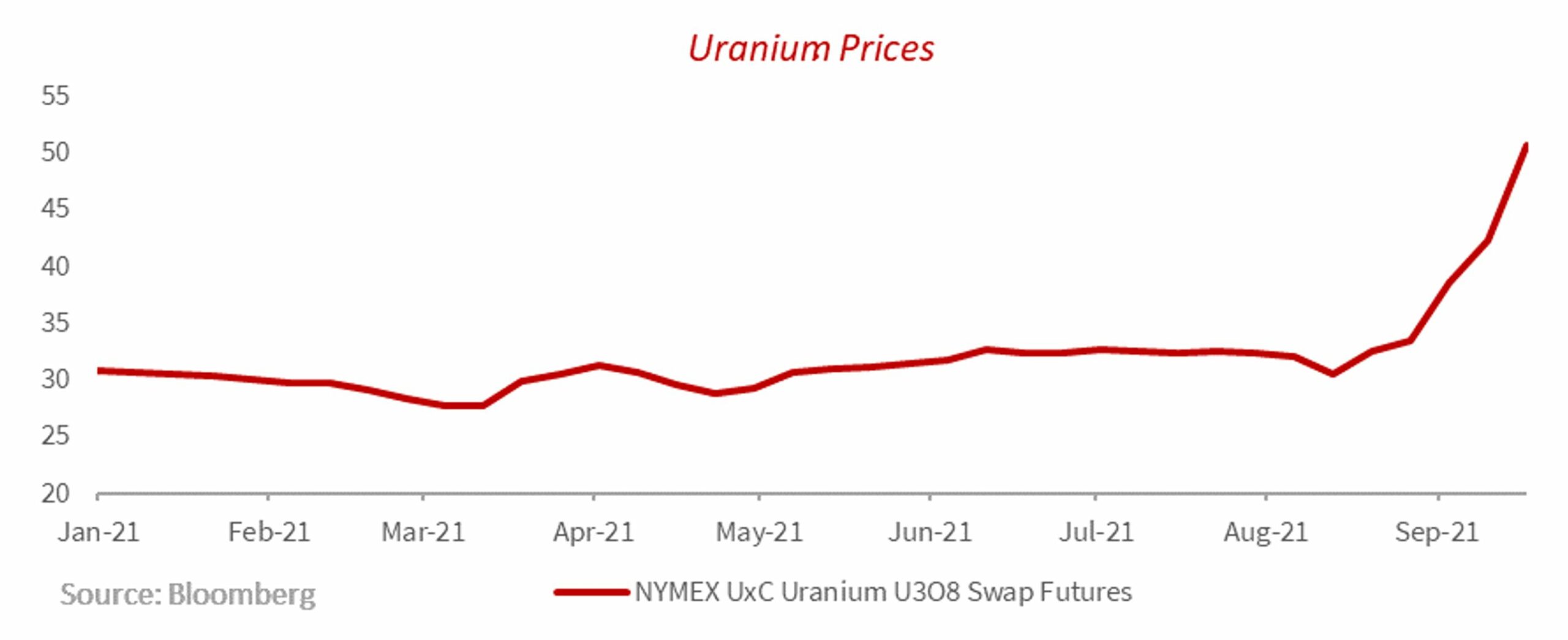

Spiking uranium prices in recent weeks is but one example of a slew of commodities that may have their own idiosyncratic climate-related narrative but can be summarized succinctly through a straightforward storyline.

Years of underinvestment and a structural increase in climate-related demand for lithium, cobalt, copper, uranium, and aluminum will see each of these commodities in structural deficits for years to come. The only solution until the inevitable supply response occurs is higher prices.

Speculation will add to the fervor, and we should routinely see spiking prices and overshooting, but the underlying imbalances will remain for years in many sectors. In the past week, I have debated with clients about the geopolitical implications for countries like Chile as both the United States and China vie for the stable supply of copper. Will the United States develop its own lithium and copper strategic reserves just as the Chinese have? This makes perfect sense as it will be the only way to protect the US auto industry that is looking at a microcosm of the potential problem it could face if GM and Ford cant access the commodities it requires to produce the next generation of electric vehicles. The semiconductor shortage creates manufacturing challenges, but cars are still sold even if they don’t have all the features. Ford can sell an F-150 minus a few chips. They cannot sell an electric vehicle if it doesn’t have a lithium battery or copper wiring.

Huge increases in demand for lithium and copper and a multi-year supply response could see parabolic price spikes in the years ahead. However, price gains should not be limited just to “clean commodities.” I am convinced that estimates for the sale of 30m electric vehicles in 2025 underestimates the likely demand for EVs. Let us assume it is double that number. By 2025, we will have well over 1.5bn vehicles worldwide, the vast majority of which will still require petrol or diesel. The lack of investment in new oil infrastructure creates a scenario of a supply-constrained oil market for decades to come. A world of 60m EVs and $150 for a barrel of oil are not mutually exclusive.

The inflation paradox

The world I am describing is where commodity prices spike due to “climate friction.” A global economy where the demand for decarbonization leads to enormous supply chain disruptions leading to shortages of essential commodities required for the energy transition. This takes us to the most important monetary policy question of the next decade, a question so much more critical than tapering or the COVID response.

With Central Banks prioritizing climate change when determining monetary policy, can the ECB, the Fed, and other major central banks ignore the inflation produced as part of the energy transition?

This is a world where Jean Claude Trichet would be in a panic. $150 oil or copper selling at $20,000 a tonne would historically prompt central banks to restrict liquidity conditions. However, raising rates in the face of climate-induced inflation seems like an exercise in self-sabotage. Especially for the ECB, this seems at odds with the strategic review. Is there a way that the ECB or Fed can look through the inflation generated via a strategic priority? This is a complicated scenario to assess, and as we stand today, we are left with more answers than questions.

For example, how on earth would you strip out climate inflation? Copper doesn’t just go into electric vehicles. It is a major input into commercial and residential property. Can a central bank ignore a sharp increase in the cost of construction? What about the price of oil regarding the production of plastics. Plastic demand is predicted to continue to increase until at least 2030. Can we ignore a doubling of the oil price and the impact it would have on the cost of packaging? It is not as simple a stripping out the price increase driven by the energy transition.

Conclusion

The response by the Fed and the ECB to the pandemic was to look at inflation as transitory. This is sound, and I feel it will be vindicated. The global supply chain has faced an unprecedented disruption, but the flexibility and efficiency of the supply chain will see it snap back to equilibrium in the quarters ahead. In this regard, the global economy is simply remarkable.

When I think about normalization, I think about a return to what the global economy looked like prior to the pandemic and how financial assets performed. This makes sense because if the global economy is going to return to a pre-pandemic framework, isn’t it logical that the pricing of assets reflects that economic environment?

What did the global economy look like before the pandemic? It was a world of slower growth, disinflation, and deteriorating developed world demographics. A world where the EU and Japan had negative interest rates and the US had spent most of the decade with cash rates below 2%. China was the growth outlier, but growth rates were gliding lower, just as they were in the majority of the emerging world despite the historically low cost of funding.

However, the next decade will not be like the last because of the determination to deal with climate change. It will see trillions of dollars of public and private investment in decarbonization and energy transition.

While the global economy is efficient, the scale and scope of the energy transition almost guarantees supply shocks in many commodities and are not limited to those metals central to infrastructure buildout. The underinvestment in fossil fuels could well see spiking prices in the years ahead. Traditionally, this would have led to central banks raising interest rates and tightening liquidity conditions. However, tightening policy due to the consequences of dealing with climate change seems self-defeating.

Can central banks look through commodity-induced inflation in the same ways they treated pandemic-related price spikes as transitory? It is the most important question in central banking for the next decade.

From an investment standpoint, keep it simple. The ultimate inflation hedge for the next decade will be commodity baskets and exposure to the equities of the firms that supply the world with copper, lithium, and aluminum. With commodities tactically rolling over, this will be the opportunity to add to exposure over the next few weeks. A plummeting iron ore price is creating value in companies like BHP and RIO. Stalling copper prices should produce opportunities in the likes of Freeport.

We do not know how central banks will deal with climate inflation, so therefore the response of the bond market to higher commodity prices is also questionable. Shorting fixed income is the pavlovian response to inflation fears. Over the next several years, it may not be that simple.